Five Nights at Freddy’s was directed by Emma Tammi, written by Tammi, Scott Cawthon, and Seth Cuddeback, who base their script on Cawthon’s games of the same name; it stars Josh Hutcherson, Piper Rubio, Elizabeth Lail, Mary Stuart Masterson, and Matthew Lillard. It’s about a newly hired night supervisor surviving his new job while learning about the parent company’s troubled past.

The Plot: Nearly a decade’s worth of lore, mysteries, and theories (you know what I’m referring to) separate the Five Nights at Freddy’s movie from the games. Despite the filmmakers having the opportunity to prune the best ideas for a script, the feature’s plot is surprisingly bland.

After getting fired for mistakenly beating up a father in front of his kid, Mike’s (Hutcherson) job opportunities have shrunken. No one has an ideal solution, not even career counselor Steve (Lillard, stealing every second he’s on screen). However, he points Mike towards a gig at the defunct Freddy Fazbear’s Pizzeria as a security guard, watching over the animatronics and shooing vagrants. Realistically, this is all that was necessary to facilitate an unfurling tale of corporate mismanagement and lost innocence, but Tammi, Cawthon, and Cuddeback opt to throw in some unrewarding subplots instead. One of them is thankfully treated like a subplot, that being Mike’s guardianship of his younger sister Abby (Rubio) and his custody battle over her with their aunt, Jane (Masterson) which loops back into the grand scheme, but the others just detract from the high concept.

Seizing the supposedly quiet nightshift allows Mike to sleep, but instead of making this strictly into an element of horror, Five Nights at Freddy’s instead uses it to introduce a distant case of missing children tied to the company. While one might think that prowling cop Vanessa (Lail) would incite investigation, it instead comes via a sort of dream projection where Mike can view more of the past than he thought possible. The destination isn’t as surprising as anticipated, and a further split in the film’s scope comes when a group of criminals break into the discount Chuck E. Cheese, redirecting the narrative into something more straightforward to close on.

Worldbuilding is a priority here, but the writers should’ve gone with the original game’s storytelling methods: laying out a template introducing several questions, answering most, and repeating. Instead there’s just too much going on for such a concept.

The Characters: Over-explanations continue to undo creative successes from the game franchise in the character department across the board. Time spent dealing with the same old protagonist drama makes one yearn for a stripped back cast.

Part of what made the game (at least the first one, anyway) easily accessible is the player character’s almost nonexistent relevance. At first, Five Nights at Freddy’s seems to agree, effectively explaining and motivating Mike’s presence at the dead-end job with a loose temper and a sibling to care for. More is gleaned, but every following expansion makes the lead less and less interesting, as a cliche backstory and life story lessen any potential vicarious viewing.

Similarly, Abby and Jane are paid too much mind throughout the runtime of FNAF considering their thinness. Abby’s personality is typical for kids under the supervision of siblings in movies; focusing on drawing and talking to imaginary friends while wishing her situation was better. Familiar as that take is, she’s a quickly understood motivation, which suffices. Jane is a cartoon though, taking any and all measures to steal the kid away from her brother to get a tax incentive for guarding a child. Her efforts receive a significant amount of screentime, with the writers hoping to create a compelling legal case in the middle of a story about lost kids and killer animatronics.

None of these characters are who audiences are most likely anticipating, and it’s all the more frustrating when Tammi sticks with them as though they’re more than just reheated slices of banality.

The Horror: Beguilingly, the adaptation of a horror video game franchise isn’t all that interested in using the assets it has to create much dread. While there are moments that effectively realize the concepts on-screen, they’re rather rare.

Jumpscares are the bread and butter (pizza and fries?) of the games, and the movie almost matches the acuity that Cawthon presented them with in the first place. For those who don’t know, the animatronic mascots of Freddy’s Pizzeria get a little quirky at night, wandering around courtesy of their recharging batteries. The simple realization of something static, decommissioned years ago, being somewhere other than where it was left is effectively unnerving. Add Mike’s ignorance to the facility’s past, and each slight change in placement becomes a source of fear. Sometimes Tammi plays this trick solely on the audience, which feels a little overused, but it’s still a solid scare tactic.

Unfortunately, the other primary method of horror doesn’t translate across mediums. Spectral children tied to an incident long passed fill Mike’s dreams while he’s on the clock, and, without a somewhat novel presentation, the movie can’t find a way to make them do something different. They stare ominously, lead without communication, and occasionally act as jumpscare sources, but Five Nights at Freddy’s lingers on them for so long that these moments become awkward instead of uneasy – not that an idea that familiar was ever effective in this film.

Obviously the machines come into play, but the numerous subtle scares deflate when it becomes clear that the movie can’t play up its gimmick. Gore and bloodshed would be unnecessary, but a greater payoff between Mike’s woes and the mechanical animals to make up for an ineffective middle stretch was needed.

The Technics: Although the feature had been gifted an already realized source, it’s curious how little of Five Nights at Freddy’s mechanical merits are worth mentioning. Though slavish visually, the spirit is gone.

While the games maintained a faint but detectable undercurrent of black humor, Tammi, Cawthon, and Cuddeback couldn’t keep consistent for the screen adaptation. Almost relentlessly dour, the only real jokes come at the expense of Masterson’s Grand Guignol performance, but with the writers’ themes of burnout, child kidnapping, and domestic rivalry, it’s hard to imagine where any levity could otherwise stem from. Additionally, the runtime is stretched thinner than the story and characters can afford to uphold, with endless shots and (nine months) pregnant pauses in between the majority of individual lines making an average-length movie feel interminable.

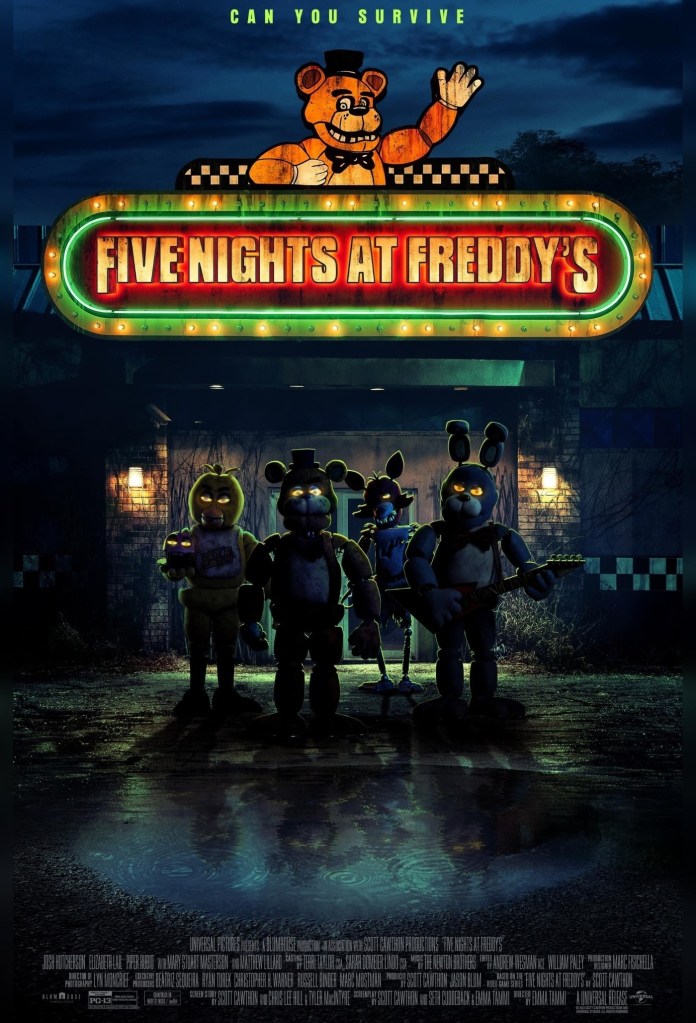

At the very least, the picture is visually engaging, with the quartet of animatronic animals superbly manifested in physical form by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. The level of detail is terrific, with each stiff movement comparable to those unsettling creations that inspired them. Production design by Marc Fisichella is equally praiseworthy, taking care to balance the uncanny fake settings with lived-in detail, creating a recognizably spooky setting.

It seems as though the filmmakers really want Five Nights at Freddy’s to be something more than it is, with an unengaging plot, a lack of focus on horror, and stiff characters, it doesn’t succeed in conveying the merits of the idea of murderous nightmare machines.

39/100

Misc details

Release date (US): October 27, 2023

Distributor: Universal

Runtime: 109 minutes

MPAA rating: PG-13

Leave a comment